November 1984 will remain one of the darkest chapters in the history of free India. More than 3,000 innocent Sikhs were murdered on the streets of Delhi and several hundred more across India. Rampaging mobs, often instigated by political ringleaders, pulled Sikh men by their long hair out of their homes, garlanded them with burning tyres, chopped off ears and noses and clapped in glee. Homes, taxi stands, shops went up in smoke spirals that rose high into the winter sky to the accompaniment of ghoulish howls. The state machinery stood silently by: two Sikh guards had assassinated then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi for desecrating the hallowed Golden Temple by sending in army tanks; the carnage in Delhi was seen as a vicious act of revenge, the anger was to be allowed to spend itself.

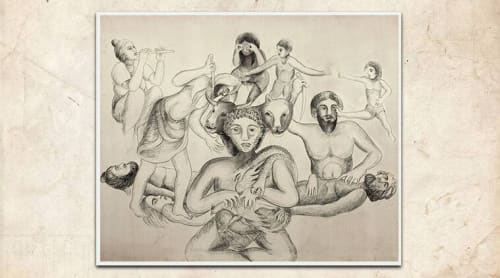

In that dark first week of November, the trauma of Punjab’s partition was played out in all its horror again. Only this time it was in the heart of Delhi. There was no new nation being born, no new destination to run to. This was death in your own country. Sikhs hid in cupboards and lofts, under their neighbour’s beds, even in embassies. Many chopped off their long hair to hide their identity. Some took out rusty kirpans and service revolvers to prepare for a final stand. But for the 3,000 there was no hiding, no fighting. Their hands clasped in pathetic appeal, their eyes white with fear, in sight of their wives and daughters and sisters, they died meaningless, violent deaths.