Continuing our series of conversations between artists, we bring together works by Susanta Mandal and Ram Kumar. The exhibition presents two takes on the grid, the device that art historian Rosalind Krauss declared as the ‘modernity of modern art’. Landscape in Ram Kumar’s works is distilled into a grid of dynamic lines and planes, always askew and in movement. In Susanta Mandal’s installation it returns to the mundane world, as a series of exposed pipelines, the invisible and precarious lifeline that keeps our homes running.

Susanta Mandal’s kinetic installations include both ephemeral materials and low tech contraptions with their exposed mechanics. His primary interest is in movement and his installations explore both virtual and physical movement through motors, videos, photographs, light and shadow, among other materials.

On exhibit are two works - It doesn’t bite II and How long does it take to complete a circle? – that juxtapose the static structures made from glass pipes, steel plates and rods with ephemeral materials like bubbles. They take on a performative quality: In this quasi-scientific, lab-like-setting, the bubbles escape from the structure to explore their own free form, if only for brief moment, before dissipating. Another work looks at a series of drawing that explore the physicality of compressed air.

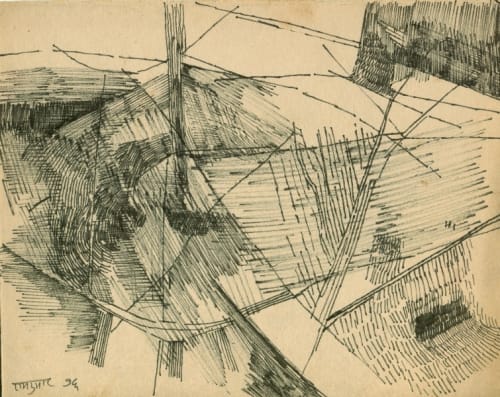

On another wall hang five drawings by Ram Kumar from the early 1970s. By the early 1960s Ram Kumar had already abandoned the figure inspired by his travels to places like Benaras, Sanjoli, Kashmir, Ranikheth and Greece. These drawings speak of the underlying structure, the grid that Ram Kumar deploys in his paintings which suggest a hint of landscape now turned into a system of interlocked lines and planes. Always askew, the drawings suggest movement and exploration. The link between the perceptual and the conceptual, between semblance and structure, in these drawings and in Ram Kumar’s works in general is something which critics like Ranjit Hoskote and Richard Bartholomew, have written so eloquently about.

The phrase Reflected Verses comes from the cult literary figure Anna Akhmatova’s homage to her friend Boris Pasternak. Four poets meeting secretly in Stalinist Russia, consigning each other’s poems to memory so as to allow their works to live on. Poetry acquires another dimension when spoken in the presence of someone, tinged with the sharpness of memory and experience. Soliloquies turn into intimate conversations, incomplete utterances, spirited debates, even strident manifestos that remind us of the ambition of art to outlive its makers. They spill over time and place, shining light on forgotten corners, animating new readings and urgencies. Reflected Verses is a series of juxtapositions that act as provocations to the works on display and the spaces they are exhibited in.