Manjit Bawa: Kala Bagh: D-40 Defence Colony, New Delhi

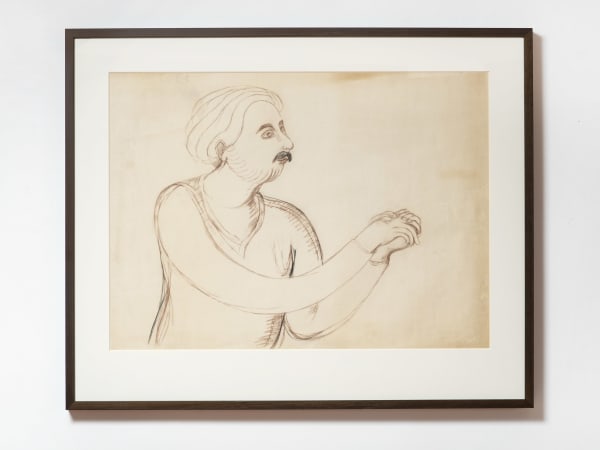

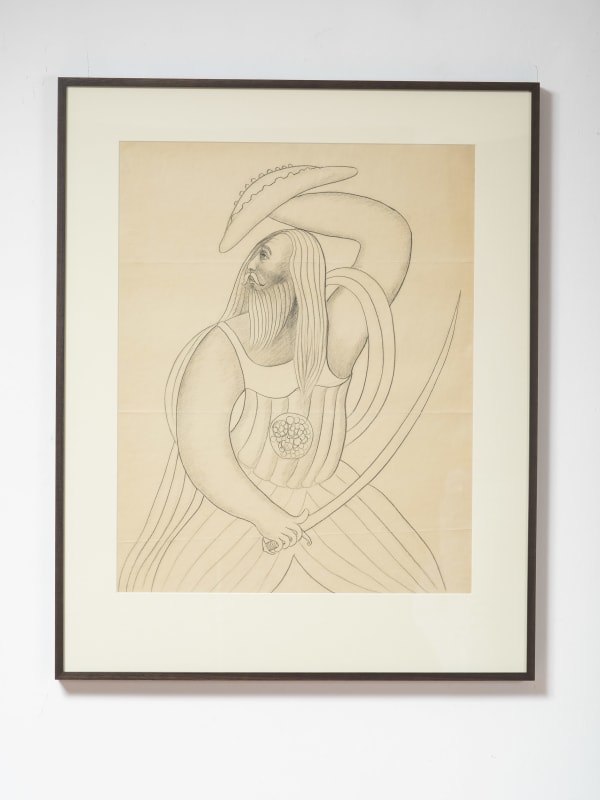

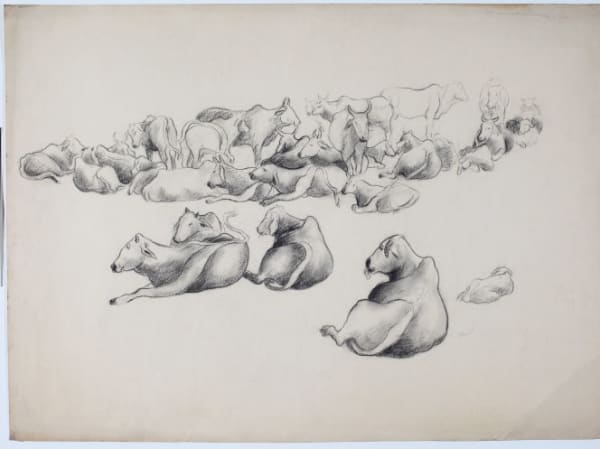

Manjit BawaUntitledCharcoal on paper36 x 23 in

Manjit BawaUntitledCharcoal on paper36 x 23 in Manjit BawaUntitledCharcoal on paper30 x 23 in

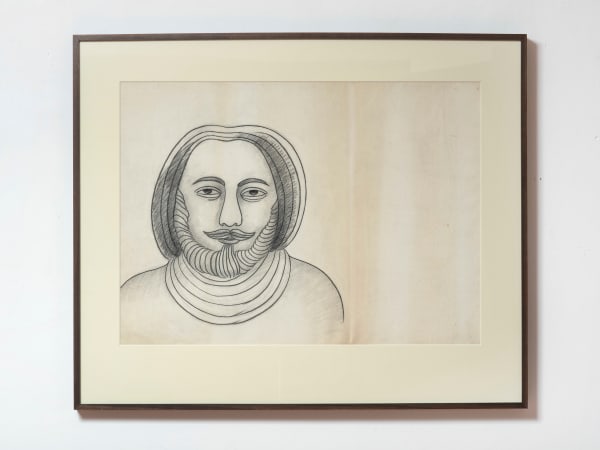

Manjit BawaUntitledCharcoal on paper30 x 23 in Manjit BawaUntitledCharcoal on paper28 x 22 in

Manjit BawaUntitledCharcoal on paper28 x 22 in Manjit BawaUntitledCharcoal on paper29.5 x 22 in

Manjit BawaUntitledCharcoal on paper29.5 x 22 in Manjit BawaUntitledCharcoal on paper36 x 23 in

Manjit BawaUntitledCharcoal on paper36 x 23 in Manjit BawaUntitledCharcoal on paper20 x 30 in

Manjit BawaUntitledCharcoal on paper20 x 30 in Manjit BawaUntitledCharcoal on paper13.5 x 21 in

Manjit BawaUntitledCharcoal on paper13.5 x 21 in Manjit BawaUntitledCharcoal on paper18 x 23 in

Manjit BawaUntitledCharcoal on paper18 x 23 in Manjit BawaUntitledCharcoal on paper18 x 23 in

Manjit BawaUntitledCharcoal on paper18 x 23 in Manjit BawaUntitledCharcoal on paper11 x 14.5 in

Manjit BawaUntitledCharcoal on paper11 x 14.5 in Manjit BawaUntitledCharcoal on paper11 x 14.5 in

Manjit BawaUntitledCharcoal on paper11 x 14.5 in Manjit BawaUntitledCharcoal on paper21.5 x 26.5 in

Manjit BawaUntitledCharcoal on paper21.5 x 26.5 in Manjit BawaUntitledCharcoal on paper22 x 30 in

Manjit BawaUntitledCharcoal on paper22 x 30 in Manjit BawaUntitledCharcoal on paper28.5 x 42 in

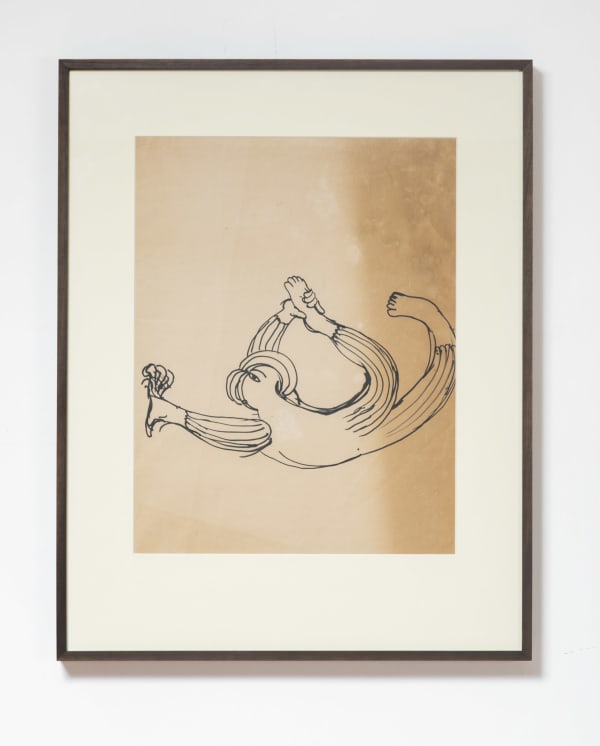

Manjit BawaUntitledCharcoal on paper28.5 x 42 in Manjit BawaUntitledUnsignedPen on paper22 x 27 in

Manjit BawaUntitledUnsignedPen on paper22 x 27 in Manjit BawaUntitledSignedPen on paper41 x 29.5 in

Manjit BawaUntitledSignedPen on paper41 x 29.5 in Manjit BawaUntitledDrawing on canvas59 x 132 in

Manjit BawaUntitledDrawing on canvas59 x 132 in Manjit BawaUntitledDrawing on canvas59 x 142 in

Manjit BawaUntitledDrawing on canvas59 x 142 in Manjit BawaUntitledCharcoal on paper28 x 38 in

Manjit BawaUntitledCharcoal on paper28 x 38 in Manjit BawaUntitledCharcoal on paper22 x 30 in

Manjit BawaUntitledCharcoal on paper22 x 30 in Manjit BawaUntitledCharcoal on paper30 x 22 in

Manjit BawaUntitledCharcoal on paper30 x 22 in Manjit BawaUntitledCharcoal on paper28 x 22 in

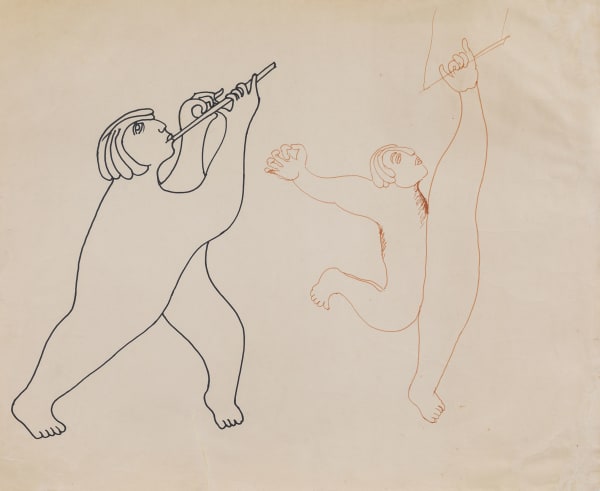

Manjit BawaUntitledCharcoal on paper28 x 22 in Manjit BawaUntitledUnsignedMixed Media on paper22 x 30 in

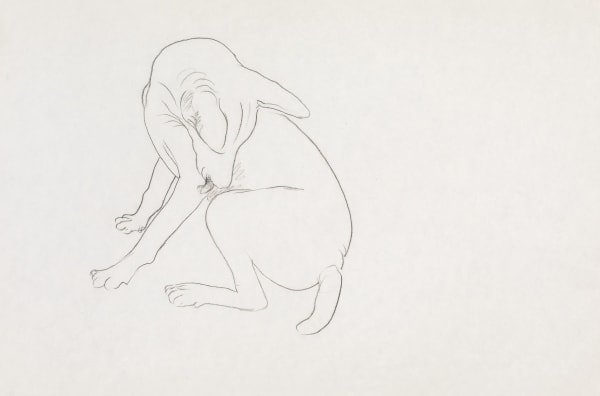

Manjit BawaUntitledUnsignedMixed Media on paper22 x 30 in Manjit BawaUntitledPencil on paper28" x 22"

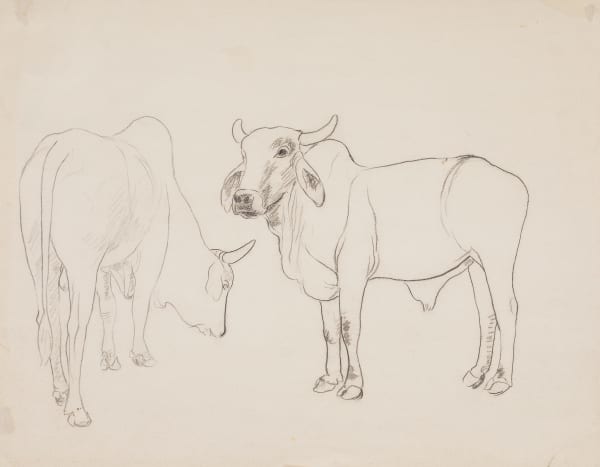

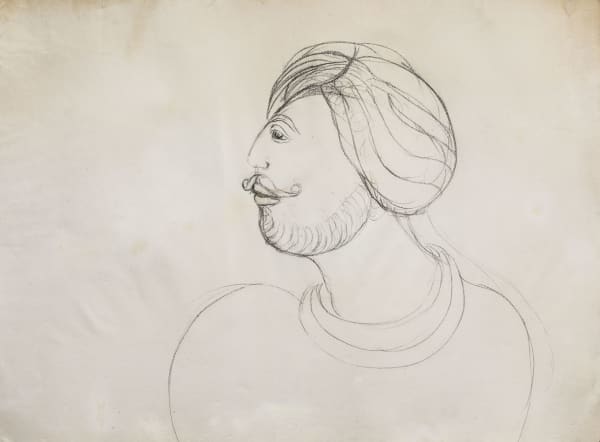

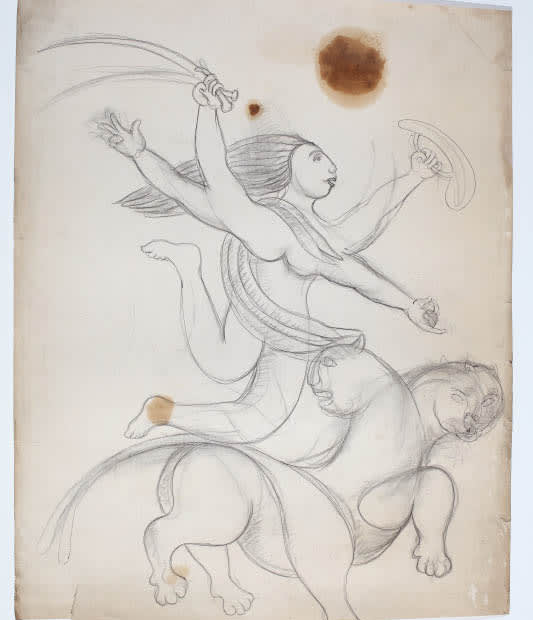

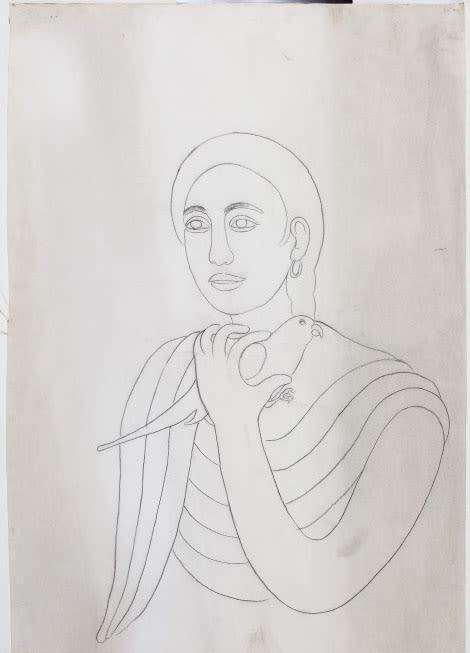

Manjit BawaUntitledPencil on paper28" x 22" Manjit BawaUntitledPencil on paper39.5" x 21.5"

Manjit BawaUntitledPencil on paper39.5" x 21.5" Manjit BawaUntitledPencil on paper22" x 30"

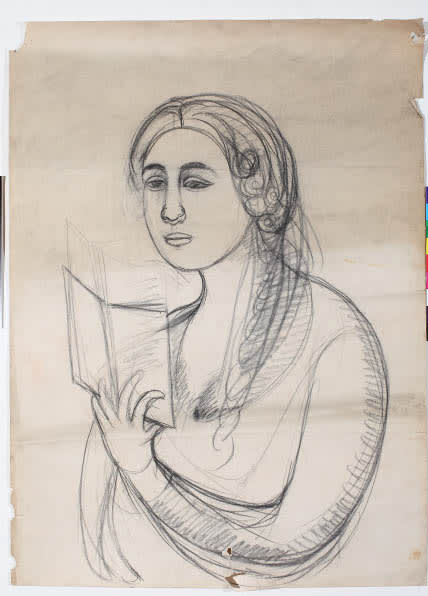

Manjit BawaUntitledPencil on paper22" x 30" Manjit BawaUntitledPencil on paper30" x 20.5"

Manjit BawaUntitledPencil on paper30" x 20.5" Manjit BawaUntitledPencil on paper36" x 23"

Manjit BawaUntitledPencil on paper36" x 23" Manjit BawaUntitledCharcoal on paper30" x 22"

Manjit BawaUntitledCharcoal on paper30" x 22" Manjit BawaUntitledColour pastel on paper22 x 30 in

Manjit BawaUntitledColour pastel on paper22 x 30 in Manjit BawaUntitledCharcoal on paper22 x 30 in

Manjit BawaUntitledCharcoal on paper22 x 30 in

Born in 1941 in Dhuri, Punjab, Manjit Bawa received a national diploma in fine arts from the School of Art, Delhi Polytechnic in 1963 and a diploma in silk screen painting from the Warden Institute of Essex, England, in 1967. In the late sixties, Bawa worked as a serigrapher in London and even taught painting at the Institute of Adult Education, England. In 1998, he started the organization Sama’a with Ina Puri to promote art and artists.

Over his career the artist attended several art camps including the Lalit Kala Akademi sponsored artist’s camp in Chennai, Graphic Camp 3 and a serigraphy camp in New Delhi, a printmaking camp in Bhopal, a graphic workshop at the Hokkaido Museum in Japan, among others.

Some of his notable posthumous exhibitions include ‘Let’s Paint the Sky Red’ at Vadehra Art Gallery, New Delhi (2011); ‘Time Unfolded’ at the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi (2011); ‘Dali’s Elephant’, Aicon Gallery, London (2010), to name a few. In his lifetime he participated in a number of solo shows, including Sakshi Gallery, Mumbai (2006, 2005); Jehangir Art Gallery, Mumbai (2005); Bose Pascia Modern, New York, (2000); and Fine Art Gallery, Mumbai (2000), among others. His group shows include the Centre for International Modern Art, Kolkata (2008); Anant Art Gallery, New Delhi (2005); Gallery Espace, New Delhi (2004); and the Centre for International Modern Art, Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata (2001–03), to name a few.

The artist was also the recipient of the 1st Bharat Bhawan Biennale in Bhopal in 1986, the All India Exhibition of Prints and Drawings, Chandigarh, in 1981, the National Award, Lalit Kala Akademi, New Delhi in 1980 and the Sailoz Mukherjee Prize, New Delhi in 1963.

The artist died in December 2008.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Manjit was one of my closest artist friends and we spent a lot of time together. I observed Manjit painting and drawing from close quarters. We exchanged thoughts on our practice and experiences. As I am neither a historian nor an art critic, I write these few passages as an artist about the period when I saw Manjit working, from the late 70s onward.

Back then, I often visited Manjit’s house and stayed overnight. Mornings in Manjit’s house revealed the most about his way of relating to life and form.

He played music on large speakers, we sipped tea and talked as he drew on a sketchpad. Ravi, his son, sat near us, almost embracing one of the large speakers. Ravi was unable to hear sounds but his body responded to the vibrations. He listened to the music through his body. Ravi eagerly waited and prodded his father to make this the first event of the morning.

Linking this experience with Ravi, where his body was infused with music, I believe that Manjit invested the body in his paintings with musicality. This gave his images a particular sinuous and lyrical linear contour.

Ravi at that age didn’t have much control over his limbs. Manjit gradually taught him balance through cajoling and fun games. The transformation has been miraculous. Ravi is independent and he is able to walk to the shops, etc. with confidence, by himself.

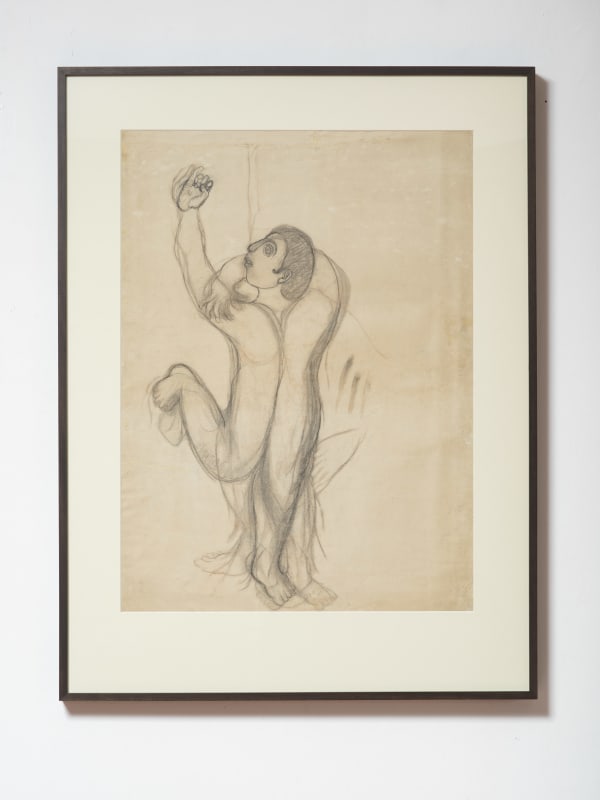

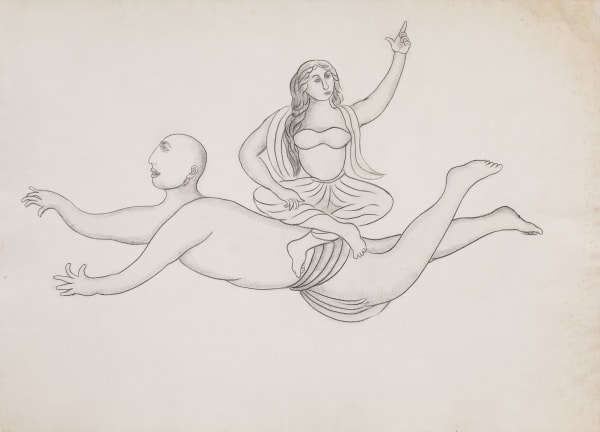

I am impelled to link Ravi’s training of balance to Manjit’s stylisation of the human figure, an aspect of his works to which I am drawn most. What captivates me is the nature of balance in those works that the body is trying to find.

It is a precarious balance. A delicate balance arrived at without the supporting skeletal frame, where the split halves of the body seek to counterbalance each other in balletic gestures. This makes for a peculiar kind of viewing experience: you feel the slight unease in your own body which is tempered by the sheer visual seductiveness of the artwork. I am reminded of a passage I read somewhere, perhaps by Faulkner, who said, “pull up your chair to the edge of the precipice and I will tell you a story.”

“ I don’t like sharp corners and straight lines”, Manjit said. Even the flute in Manjit’s paintings is not drawn with a straight line. There is some aspect of Kindchenschema, a soft roundedness which endows the face with an endearing look, which is more evident in drawings and paintings of small, young boys and girls. Manjit told me he observes his younger child Bhavna playing games and he draws her as he drew Ravi.

Once (when) I asked him what was the earliest memory of his father. He said “A puff of dust”, and I recalled being mesmerised by the puff of breath from the mouth of a lion, which birthed a goat in the air. This painting was in the first solo exhibition of Manjit’s canvases, held at the Dhoomimal Gallery. The ‘puff of dust’ was the small dust cloud left close to young Manjit’s eye by his father’s horse as it galloped off, leaving home to attend to some chore. The little cloud of dust contained a potency, the absent father, energy, power and speed… the imaginal breath of the lion I believe was born of this.

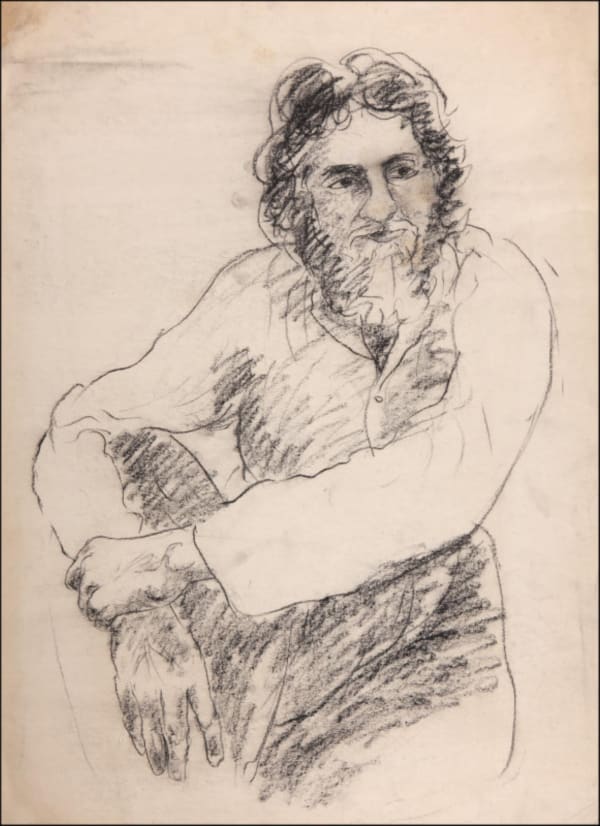

I had seen some of Manjit’s early charcoal drawings done in London. Bodies, with their corporal weight held firmly and securely in place by the gravitational pull of the earth. In a conversation, Manjit once spoke about how he had arrived at his new figuration where the body floats in weightlessness. He said the entire body had to be constructed anew. He began with the smallest component of the body, a fingernail. Manjit made many silk screen prints with several variations of the fingernail. From there, on a small pad and sometimes scraps of paper, he developed the complete figure, shading the rounded limbs with a pencil and often a ballpoint pen. The small format allowed him to try out variations during any short breaks, often while chatting over a cup of tea. Corrections were made by overdrawing rather than rubbing out: the curve of the little finger bent a little more, the elbow rounded, all by a difference of the merest millimetre. One can see such corrections made in pencil under the paint layer in some large canvases too.

Ideally, Manjit wanted to begin his painting early in the day. He liked to mop the floor himself at his Ghari studio, he would then settle down cross legged on the floor and play for a short while on his flute. It was as if this put him in a zone to arrive at the desired form and tones in his painting.

Colour for the background and the figures was mixed in a bowl, adding one colour then another and changing a few times the proportions of the colours until he was satisfied with the tone. The colours were calibrated somewhere between the sparkling light that dazzles the eye and the dullness of a muted colour. Manjit said, as opposed to the energetic gestural brushwork of his earlier paintings, where he didn’t have the patience to remove a black from the canvas when he wanted to change it to white but covered the black with consecutive layers of white, he now wished to cover the large expanse of the flat background using a thin pointed brush, two layers of the same colour, painted thus, produced a soft glow. Animals and other protagonists seemed to magically emerge, conjured up from this gentle sheen of colour field.

Ranbir Kaleka

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Junglebatta – Light in the Deep, Dark Forest

Many years ago, Manjit related to his young daughter Bhavna the story of a boy called ‘Junglebatta’, or the light in a dark forest. The essence and meaning of ‘light’ was what Manjit was also seeking to find as part of his inner journey. His love of music and Sufi philosophy had woken a desire in him to go beyond the physical world and search for a deeper truth that existed beyond the seeming reality around him.

He struggled to interpret his thoughts into his paintings but it would be years before he finally understood how it had to be done. “I’m going to paint the Kala Bagh, the dark garden (Through which the light shines) but I’m not ready for it yet”, he would often say. In the meanwhile, he continued to paint his canvases that were already sending messages of his ultimate philosophy.

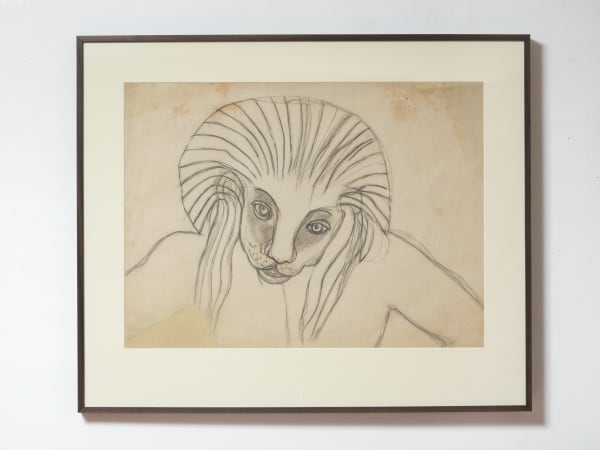

All living being in existence were linked with one another through love and integration of identities. All beings were reflections and echoes of one another, merging and mingling. His drawings sought the commonality through the physical forms he created. Thus, hair, drapery, lion’s mane, snakes, fingers or trees could have a common stylization (Nos 5,6). Elephant trunks, scarves, bull tails, lion tongues or snakes were unified through a similar rounded undulation. Bull humps and a man’s knees could not help but have identical curves through the same principle of inter-connectivity. The absorption of one living being with the spirit of another was therefore expressed by Manjit in visual terms by a shared physical resemblance.

To reinforce the closeness between human, animals and nature, Manjit depicted their constant physical proximity (No 25). And all this while, as it were, Krishna/Ranja’s magic flute played sweetly on (No 26), filling creation with desire, the desire of fulfillment with the Ultimate Being. The dark forest/garden had to be transcended for that longing to be fulfilled.

The visualization of Kala Bagh he wished to paint clarified in his mind around 2004. It required the gradual development of Kala Bagh drawings on two large rolls of canvas, each with the length of 59x142” (5x12 ft approximately), which would eventually be turned into paintings. His studio at Golf Apartments could not accommodate such a size; besides any clumsy handling would bring creases to the canvas rolls of such large dimensions. He acquired a spacious studio space in Greater Kailash and comfortably spread his rolls there. The Kala Bagh drawings were becoming a reality. Their conversion into oil paintings was still in the future.

All the many years of man, animal and nature interaction that he had picturised in his canvases had seen a limited set of figures at play together in his works. But now, the endless length of the rolls of canvas allowed him the freedom to unharness all restraint and glide into an endless continuity of imagery and thought. Siva the Creator who is manifest everywhere and Nandi his bull, appear in various arrangements, even while the sun –another giver of life, takes on the appearance of Suryamukhi, the sunflower.

The transference of shape and appearance, and hence the commonality of all things is manifest everywhere in the Kala Bagh drawings. Shiva’s snakes coil around tree, or else, they could be curved branches. Stars appear upon cacti and become cactus flowers; peacock legs identify with branches, foliage with hands, a large rock with garment and hair…

Thus, harmony is created through displacement and identity through dislocation, sameness and oneness in all.

The panels could not be completed, nor the painting begun, for Manjit unexpectedly slipped into a coma of three years and passed on thereafter. The struggle could not be completed nor the paintings reach their finality but the intent was made clear by Manjit Bawa who had been searching for the truth of all existence.

Rupika Chawla,

April 2022,

New Delhi.